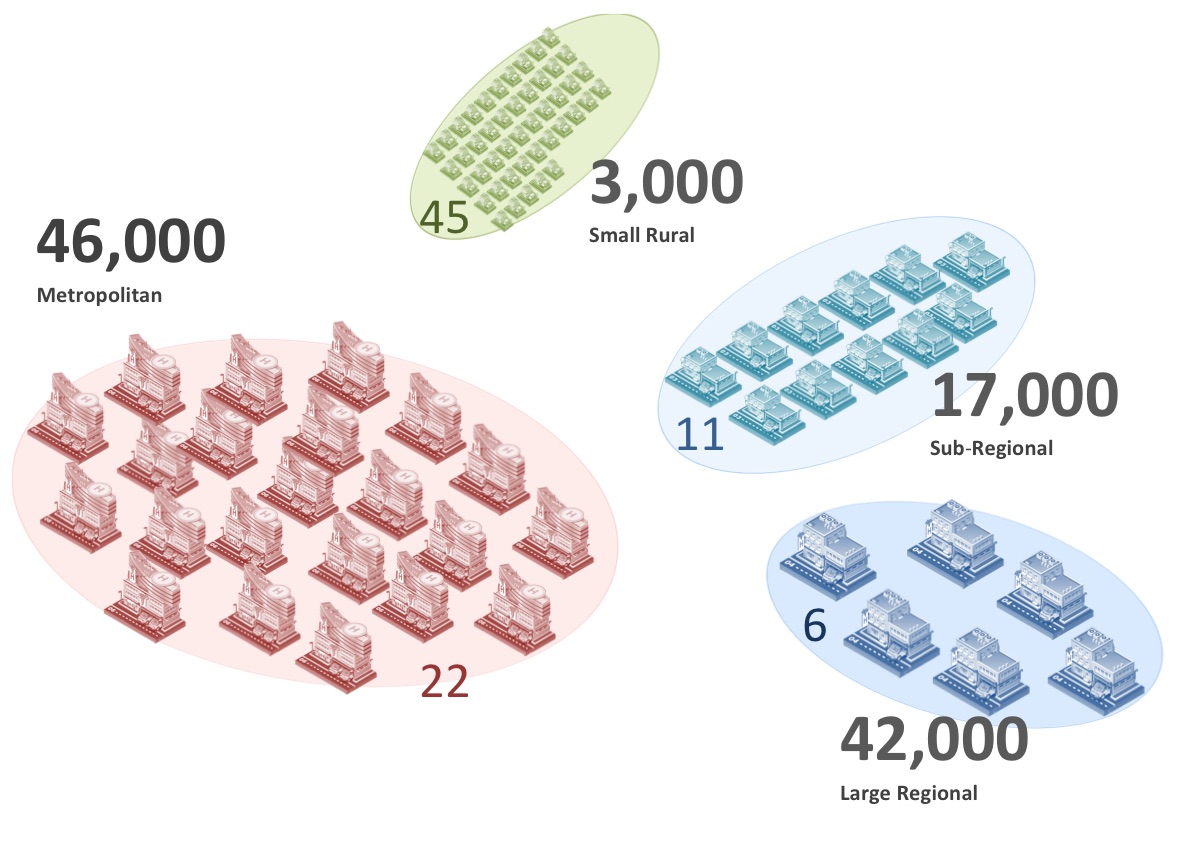

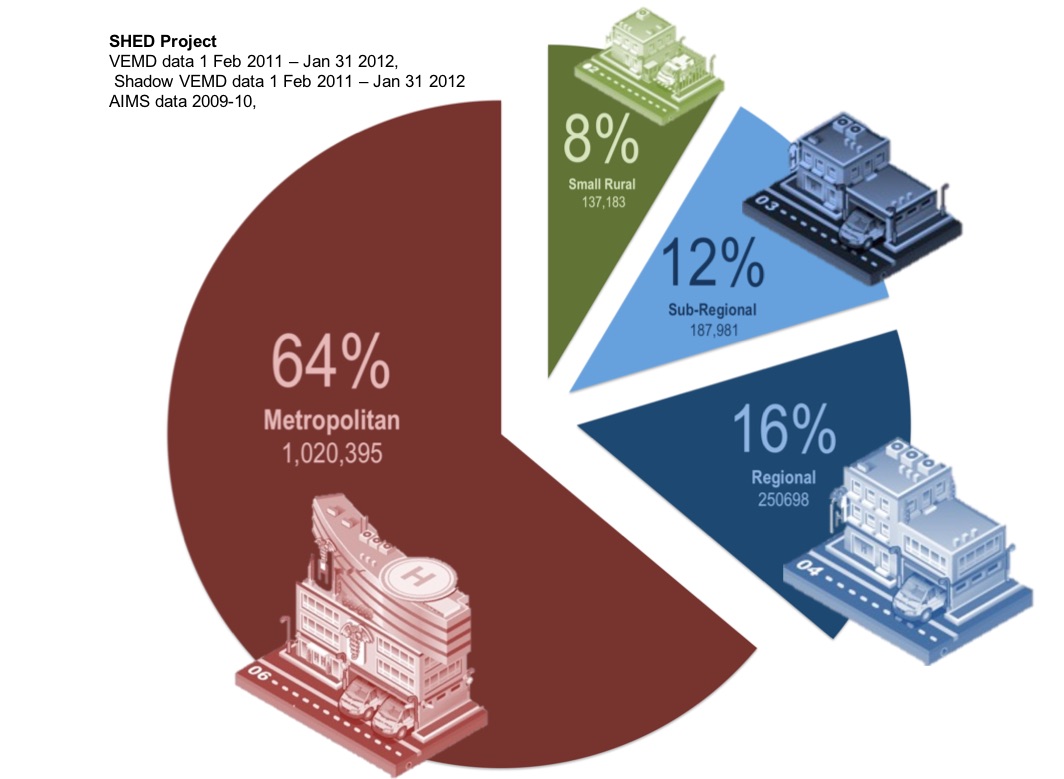

Small rural emergency departments are said to be not worth worrying about. Last post we tackled the question of whether they saw too few patients to be important. We saw, from the study described, that although each facility saw only small numbers, together they combined to be a significant proportion of a state’s emergency medical presentations.

But perhaps the patients that these small rural emergency facilities manage are not really that unwell. Perhaps these facilities provide little more than dressings and antibiotics?

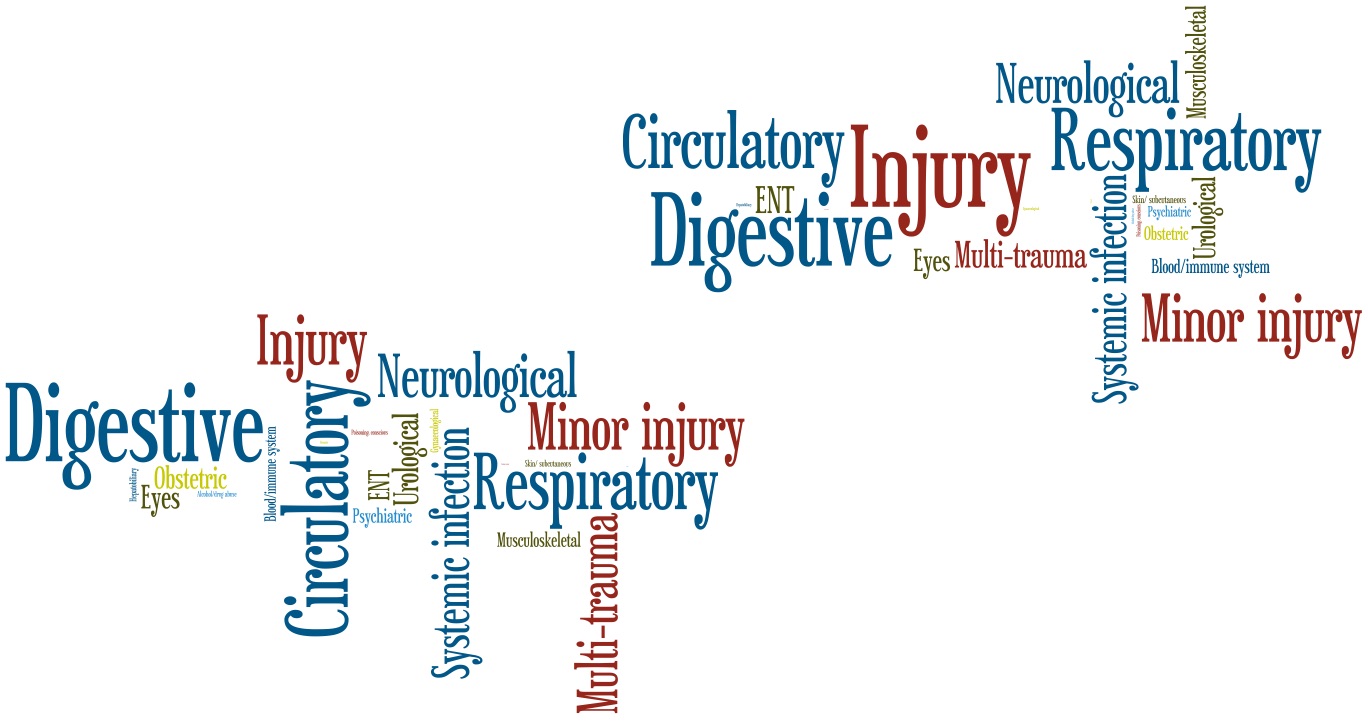

Like last post, we looked at what was happening in our state of Victoria, Australia. We turned again to the 20,000 emergency medical presentations analysed in our original study as they were managed in six small rural hospital-based emergency care facilities. We compared them to the one million patients seen in Victorian metro hospitals. We used the 28 level codes developed by the Independent Health Pricing Agency for calculating ED activity. We created two 28 by 5 charts to show the data. We have decided not to show them to you. Instead we created a Wordle.

On a wordle, each word is proportional to the number of items represented by that word. The bigger the word, the more patients presented with that diagnosis.

At a glance, you can see the the same spectrum of patients for both groups. Can you guess which is small rural and which is metro? You should be able. Respiratory, circulatory and digestive problems are common at both. So is injury, but small hospitals see more minor injury, and less multi-trauma. They are not the same, but they are not vastly different either.

It is similar with triage categories. There is a general decrease in the urgent categories as you get to smaller hospitals, but not an order of magnitude less. In metro hospitals 5 patients per 1000 were category one and 100 per 1000 category two, in the small rural hospitals it was 3 per 1000 category one and 60 per 1000 category two. In both small rurals and metros, 4 was the most common category.

This makes sense to me. I never really understood how experts could be so sure that small rural hospitals saw no sick patients when rural patients are thought to have more risk factors and poorer health, present later, don’t like to travel as much, and don’t call the ambulance as often.

So small rural emergency facilities do see similar patients to larger facilities, with about half as many critical cases. When combined they see a significant proportion of emergency medicine presentations. I think this justifies our statement that small rural emergency facilities are little in size, not importance.